The city of Kanpur lies on the Ganges in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. Within this city is a leather industry, once thriving, that is under siege. Families who have worked for generations in the city's many tanneries find themselves under threat from the Hindu nationalist movement in part spurred on by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his hyper-nationalist rhetoric. Uttar Pradesh is one of 24 Indian states with regulations on the slaughter and sale of cows. In UP, it is completely illegal to slaughter a cow, sell a cow with the intent to slaughter, or consume beef. The offense is punishable with up to 7 years in prison.

Within this codification of a religious belief in to law, hierarchies of life begin to emerge--some ancient, and some brand new. Dalits are the untouchables, seen layers below the Brahmin population. Muslims begin to suffer at the hands of the Hindu population--seen as possible violators of a religious code that their own religion doesn't follow. Tannery workers and hide transporters are viewed with suspicion by the Gau Rakshas, a right-wing nationalist organization. Cows are ranked as well--the sacred cows of Indian blood are taken to shelters and cared for, while Jersey cows--not sacred because the blood running through their veins is not of Indian descent--are left to eat garbage in the street. And the water buffalo? Not sacred at all. They are the backs upon which Kanpur's thriving leather industry has been built.

Kanpur's neighborhood of Jajmau, a predominantly Muslim area, lies on the banks of the Ganges. It is also in this neighborhood and some of the other areas outside the city center that the tanneries operate. The Ganges, a holy river for Hindus, is the fifth most polluted river in the world. Prime Minister Modi has enacted a massive river clean up initiative, but for tannery owners this isn't a good thing. For many tannery owners that we spoke to, they believe the tanneries are being unfairly targeted in the river clean up initiative--being told they are the source of many of the pollutants in the Ganga--because they are Muslim.

A cow munches on flowers as a man begins his morning prayers at a Hindu temple on the banks of the Ganges in Kanpur, India. Cows, referred to as the Gau Mata or Mother Cow in Hinduism, hold a sacred place in the religion. They are seen as the giver, the mother of life. They are to be revered, treated with respect. To slaughter or consume the flesh of a cow is against the sacred texts of Hinduism.

Tannery workers move hides soaked in chemicals through the factory courtyard at a tannery in Kanpur, India. Many of the tannery owners are Muslim, but many of the workers are Dalits, or Untouchables—the lowest caste in Hinduism, often working in jobs of waste management or dealing with animal carcasses.

Supine Yadav, 12, herds his family’s six water buffalo along the road. The water buffalo is the main supplier of leather in Kanpur’s leather industry—cow hide is only used if the cow has died naturally, or if the hide is imported from outside India. Yadav says that they keep their buffalo for as long as they continue to give milk, but once they stop producing they must sell the animal for its hide.

On a Sunday morning in the Kanpur neighborhood of Shivkatra, a cow is found dead—probably hit by a car in the early morning hours. People crowd around the cow—a small stream of blood flows from her nose and a cluster of flies dot her body. They must wait for a Dalit to arrive—sent by a government agency to move the animal. It takes hours for him to arrive, and before the body is moved he must prove the cow belonged to no one—that she was just a street cow.

Leather dries in the sun in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India. Leather is recognized under the Make in India program created by the Indian government, but the industry is suffering because of regulations surrounding environmental impact of tanneries and fear based around rising Hindu nationalist attacks against those who work in the leather industry.

President of the Small Tanners Association Hafizur Rahman stands in the yard of his tannery, where they take water buffalo ears and turn them to rawhide treats for dogs. Rahman is Muslim, but says that Kanpur compared to the rest of the country is relatively peaceful in the wake of Modi's nationalism.

Muslim children play in a park overlooking the Ganges and the banks of the neighborhood Jajmau in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India. Muslims make up a relatively high population of Kanpur, many of them working in the tannery business. Leather exporter Mohammed Shahav says that as Hindu nationalism rises under Modi, Muslims people are becoming more and more afraid—especially those dealing in the business of leather. “But we have been doing this for generations, “ he says. “What else would we do?”

Cows sit atop a Hindu temple on the banks of the Ganges in Kanpur, India. Cows, referred to as the Gau Mata or Mother Cow in Hinduism, hold a sacred place in the religion. They are seen as the giver, the mother of life. They are to be revered, treated with respect. To slaughter or consume the flesh of a cow is against the sacred texts of Hinduism.

A dead bird lies in the scraps of wetblue leather. The tanning process of turning raw hide in to leather involves many chemicals--including lye and chromium or aluminum salts. Toxic for the environment and often toxic to people, the health effects of working in the tanneries have not been well documented. More well documented are the effects of the chemicals on the environment--spurring massive tannery closures as the government works to clean the Ganges.

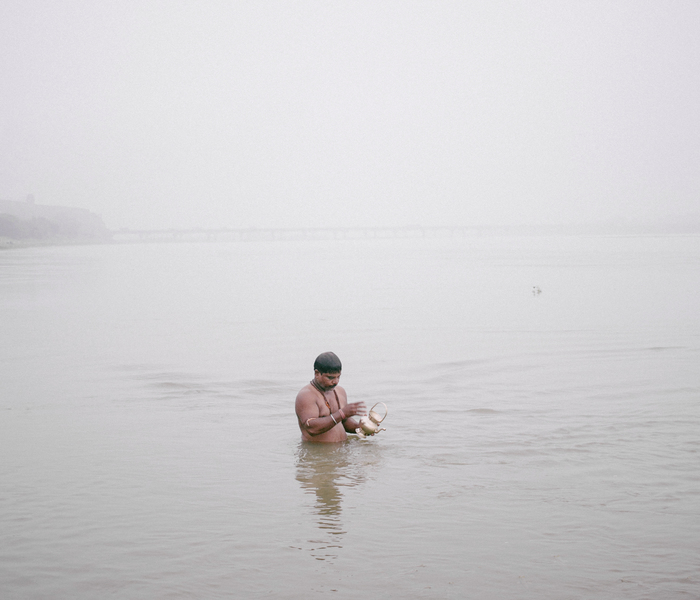

A Hindu man bathes in the Ganges in the early morning. The river holds a sacredness in Hinduism, and the Modi government has enacted a massive river clean-up. Many of the tanneries in Kanpur feel unfairly targeted in this river clean-up initiative, believing that because they are Muslim-owned that they are being hyper-regulated.

Leather scraps litter the ground--most soaked in chromium and lye. These scraps will be turned to manure that will be used locally.

Migrant workers from Raebareli, Uttar Pradesh--about 150km from Kanpur. They are all Dalits, and travel as whole family units to work in the leather scrap fields turning the scraps in to manure. When asked if their work in the leather industry makes them nervous given the recent rise in attacks spurred by cow-related Hindu nationalism, they say: "We don't have a tv and we don't read newspapers. How would we know?"

The living quarters of a migrant Dalit family working in the leather scrap fields. They tell us here they turn the scraps in to manure to be sold locally. Their tent sits within reach of the noxious black smoke flooding the field and surrounding area—it makes my eyes water and later in the day both my fixer and I are coughing up what I can only describe as deep brown tar. We were in the field maybe a half hour. The migrant family stays in this tent and works in this field for 3-5 months of the year.

Hide transporters load water buffalo hides in to a truck outside of a tannery in the Jajmau neighborhood of Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India. Especially for those who drive their trucks across state lines, this is a dangerous job. Gau Rakshas, or “cow vigilantes” who attempt to forcefully uphold the beef ban often target transporters and entangle in violent confrontations.

From left: Zahir Mohammed, Bhir Sen, Nasr Khan, Sultan Nissar sit outside a truck depot waiting for buffalo hides to be loaded in to their vehicles. They say: “The hide transporter is the person who faces the most difficulties. Anyone can bother you or stop you, and your time is precious and consumed very quickly.” They report that they are often extorted by the cops on the Bihar border.

A cow sits in the middle of the road in Kanpur. Hindus explain to me that there are degrees of sacredness within the holy cow: a cow with blood lineage outside of India, like this cow above, is far less holy because she is not Indian.

A Goshala or a sanctuary for cows, in Kanpur. Cows who have been injured or who are starving called in by concerned citizens and brought to this center. Hindus who run the Gau Shala make products from the cow's natural products (milk, urine and dung) including soap, vitamin supplements, and hair products.

From left: Thurminder Kumar, Faiz Ali, Dipen Kumar, Bhunishwar Das, Mohmadre Sik, and Bhunishwar Das sit posed in a leather factory in the Jajmau neighborhood of Kanpur—India’s northern leather capital. All are Dalits, or members of the lowest caste in Hinduism. They say they have been out of work for months as the factories sit out of work. "Muslims are okay because they own the factories, but the Dalits are who truly suffer as the workers."

. Leather scraps sit in a field.

A water buffalo waits in a trailer to be taken in to one of the large slaughterhouses just outside Kanpur. It is here that the buffalo are slaughtered and hides are cut--hides often bought by the many tanneries in Kanpur. The mechanization of slaughter with more modern machinery has made hides cleaner cut and easier to work with.

A secret skinning field in Kanpur, where animals (including cows) are brought to be skinned when they die on the street. People who work as skinners, almost always Dalits, are often the targets of violence by cow vigilantes.

People gather around the dead cow in the neighborhood of Shivkatra as she is prepared to be taken away by a Dalit. Dalits, who are almost always the transporters of corpses, are often also targeted by cow vigilantes--including just a week prior to this photo being taken in the nearby city of Lucknow.

The cow that died in the Shivkatra neighborhood is skinned by a Dalit man in a secret skinning location. The hide will then be sold to a local tannery who has deals with the skinners--cow hide selling well because it is rarer in this area of India and often more supple than that of a water buffalo.

Men rest between work at a factory in the neighborhood of Jajmau in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India. The factories are facing a decrease in business as foreign buyers worry about the Indian factory's abilities to continue producing under stringent environmental regulations and an uptick in attacks from hyper-nationalists against those working in the leather industry.

An artistic rendering of the Gau Mata, or mother cow, in the home of one of the members of the Kanpur Goashala Society.

Life imitating the artistic rendering of the Gau Mata at an ashram on the banks of Ganges in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India.